Справочник, в котором содержатся обобщенные данные о потерях флотов, а также морской авиации воюющих сторон в период советско-японской войны 1945 года. Издание охватывает все потери СССР, Японии и Маньчжурии в корабельном и судовом составе военно-морских, вспомогательных, торговых и промысловых флотов, а также в материальной части морской авиации с 9 августа по 3 сентября 1945 года.

Вы используете устаревший браузер. Этот и другие сайты могут отображаться в нём некорректно.

Вам необходимо обновить браузер или попробовать использовать другой.

Вам необходимо обновить браузер или попробовать использовать другой.

Литература по истории Японии

- Автор темы JapanX

- Дата начала

"Humanitarian Empire : The Red Cross in Japan, 1877-1945"

Author: Gregory John DePies, 2013

почитать онлайн и Скачать можно здесь:

http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6kr3c55j?view=search#page-1

Author: Gregory John DePies, 2013

почитать онлайн и Скачать можно здесь:

http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6kr3c55j?view=search#page-1

Вложения

Рецензия на книгу Джона Киндера (опубликована в Disability Studies Quarterly, Volume 36, Issue No. 4 (2016))

At the risk of exaggeration, I think it is safe to say that no disabled population is as widely honored as disabled veterans. Because their physical and mental impairments are incurred in military service, disabled vets have historically succeeded in claiming a privileged, if not preferential, status when it comes to government-sponsored relief efforts. To be fair, the road to recognition has not come easily for disabled veterans, as a growing number of scholars have made clear. Disabled veterans, like all disabled people, have been the targets of discriminatory legislation, eugenicist "health" measures, and cultural stigma, and not all time periods—or nations—are equally friendly to disabled vets. (As always, it helps to be on the winning side of a conflict.) Even so, throughout modern history, disabled veterans have tended to enjoy far more public assistance and state support than any other disabled group.

In Casualties of History, Lee K. Pennington examines the shifting status of disabled Japanese servicemen in the decades surrounding World War II. Pennington's overarching narrative—a story of encroaching state responsibility for veterans' affairs—will sound somewhat familiar to those who have read books like Deborah Cohen's The War Come Home (2001) or Beth Linker's War's Waste (2011), both of which examine Western (U.S. and European) responses to disabled vets. Prior to the 1920s, when Japanese war casualties were relatively low, the Japanese public (rather than the government) was largely responsible for "alleviating the financial hardships of crippled soldiers" (22). As the twentieth century progressed, however, the role of caring for disabled veterans shifted to the state. An important turning point came during World War I, when Japanese military and medical leaders began to embrace the Western concept of vocational rehabilitation to help disabled veterans return to postwar society as productive workers. The expansion of such programs—along with a revamped pension system and an array of other measures—"presented a categorical rethinking of war-wounded men as individuals deserving preferential" treatment, above and beyond their fellow (disabled) citizens (41). No less significant, Pennington suggests the rising support for disabled veterans helped smooth the way for future military endeavors, as Japanese society became more willing to accept high numbers of war casualties.

It should be noted that, at times, disabled veteran's history can make for pretty dry reading. In their encounters with the state, Japanese disabled veterans were forced to wend their way through a vast bureaucratic apparatus—a seemingly never-ending web of acronyms, obscurely titled programs, and long-winded pronouncements that left many wounded servicemen overwhelmed and that can leave even the most diligent social historian reaching for the NoDoz. Pennington skillfully avoids this pitfall by anchoring his discussion of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) medical system in the story of Private First-Class Saijō, a Japanese soldier who was wounded in the forearm by an exploding shell in 1939. Drawing upon his 1941 memoir, The Fighting Artificial Arm, Pennington traces Saijō's ordeal from the moment of injury, through various echelons of the medical evacuation process (his arm was eventually amputated), to Tokyo Number Three Army Hospital, the nation's "premier medico-military institution for combat amputees" (17). In doing so, Pennington challenges the view put forth by anthropologist Ruth Benedict that the IJA medical system was inadequate and that "Japanese soldiers [were] fanatics who routinely chose death over life" (58).

Many DSQ readers will likely find Chapter 5—a lengthy survey of disabled veterans in Japanese wartime propaganda and pop culture—the most interesting part of Casualties of History. Pennington points out that, unlike in Nazi Germany or the United States (both of which redacted representations of wounded soldiers from the public record), Japanese wartime culture abounded with images and stories of disabled veterans, even though the actual pain associated with bodily trauma remained largely absent. Throughout the war years, "white-robed heroes" (so named because of the robes worn by Japanese wounded soldiers during and after convalescence) were celebrated as national heroes and icons of "selfless sacrifice" (166). Pennington draws upon the work of Rosemarie Garland-Thomson and others to show how wartime Japanese culture attempted to defuse doubts about high casualty rates by downplaying the physical limitations associated with serious injury. Indeed, Pennington suggests that the "extraordinary treatment of disabled veterans in mass culture" played an important role in cementing public support for the war effort, even in its darkest hours (193).

We might imagine, then, the surprise and outrage felt by disabled veterans when they were increasingly marginalized in Japan's postwar "loser's narrative" (9). Eager to stamp out the last vestiges of Japanese militarism, the occupying Supreme Commander for Allied Powers (SCAP) dismantled the veterans' assistance system and stripped disabled veterans of their military pensions. SCAP insisted that disabled veterans did not deserve special consideration based upon their military service. They were, instead, lumped into a larger population of "war sufferers," their stories of hardship quickly eclipsed by those of bereaved families and other civilian casualties (197). In this respect, Pennington opines, disabled Japanese veterans of World War II were "doubly casualties of history"—first injured in a failed war and then forgotten by a nation eager to exorcise the ghosts of its martial past (16). It is a historical lesson that the latest generation of US disabled veterans should take to heart: nations tend to "support the troops" when it is convenient. The "white-robed hero" one day might be penniless in the streets the next.

Casualties of History ends, somewhat abruptly, in the early 1950s, and I could not help but wonder what happened next. What happened to the 60,000-member Japan Disabled Veterans Association, which Pennington tantalizingly mentions in the book's introduction (14)? Were disabled veterans left behind during the vaunted Japanese "economic miracle" of the 1960s-1980s? Did they remain "forgotten men" until the revival of interest in disabled veterans in the early 2000s? And to what extent did changing ideas about gender and sexuality shape responses to disabled veterans in the postwar years? Perhaps Pennington is already at work on a follow-up that addresses such questions. For now, though, we should appreciate the fine work that he has accomplished. Meticulously researched and thoughtfully conceived, Casualties of History is a premier work of disability history—one that deserves to be read by students and teachers alike.

References

Cohen, D. (2001). The War Come Home: Disabled Veterans in Britain and Germany, 1914-1939. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Linker, B. (2011). War's Waste: Rehabilitation in World War I America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

At the risk of exaggeration, I think it is safe to say that no disabled population is as widely honored as disabled veterans. Because their physical and mental impairments are incurred in military service, disabled vets have historically succeeded in claiming a privileged, if not preferential, status when it comes to government-sponsored relief efforts. To be fair, the road to recognition has not come easily for disabled veterans, as a growing number of scholars have made clear. Disabled veterans, like all disabled people, have been the targets of discriminatory legislation, eugenicist "health" measures, and cultural stigma, and not all time periods—or nations—are equally friendly to disabled vets. (As always, it helps to be on the winning side of a conflict.) Even so, throughout modern history, disabled veterans have tended to enjoy far more public assistance and state support than any other disabled group.

In Casualties of History, Lee K. Pennington examines the shifting status of disabled Japanese servicemen in the decades surrounding World War II. Pennington's overarching narrative—a story of encroaching state responsibility for veterans' affairs—will sound somewhat familiar to those who have read books like Deborah Cohen's The War Come Home (2001) or Beth Linker's War's Waste (2011), both of which examine Western (U.S. and European) responses to disabled vets. Prior to the 1920s, when Japanese war casualties were relatively low, the Japanese public (rather than the government) was largely responsible for "alleviating the financial hardships of crippled soldiers" (22). As the twentieth century progressed, however, the role of caring for disabled veterans shifted to the state. An important turning point came during World War I, when Japanese military and medical leaders began to embrace the Western concept of vocational rehabilitation to help disabled veterans return to postwar society as productive workers. The expansion of such programs—along with a revamped pension system and an array of other measures—"presented a categorical rethinking of war-wounded men as individuals deserving preferential" treatment, above and beyond their fellow (disabled) citizens (41). No less significant, Pennington suggests the rising support for disabled veterans helped smooth the way for future military endeavors, as Japanese society became more willing to accept high numbers of war casualties.

It should be noted that, at times, disabled veteran's history can make for pretty dry reading. In their encounters with the state, Japanese disabled veterans were forced to wend their way through a vast bureaucratic apparatus—a seemingly never-ending web of acronyms, obscurely titled programs, and long-winded pronouncements that left many wounded servicemen overwhelmed and that can leave even the most diligent social historian reaching for the NoDoz. Pennington skillfully avoids this pitfall by anchoring his discussion of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) medical system in the story of Private First-Class Saijō, a Japanese soldier who was wounded in the forearm by an exploding shell in 1939. Drawing upon his 1941 memoir, The Fighting Artificial Arm, Pennington traces Saijō's ordeal from the moment of injury, through various echelons of the medical evacuation process (his arm was eventually amputated), to Tokyo Number Three Army Hospital, the nation's "premier medico-military institution for combat amputees" (17). In doing so, Pennington challenges the view put forth by anthropologist Ruth Benedict that the IJA medical system was inadequate and that "Japanese soldiers [were] fanatics who routinely chose death over life" (58).

Many DSQ readers will likely find Chapter 5—a lengthy survey of disabled veterans in Japanese wartime propaganda and pop culture—the most interesting part of Casualties of History. Pennington points out that, unlike in Nazi Germany or the United States (both of which redacted representations of wounded soldiers from the public record), Japanese wartime culture abounded with images and stories of disabled veterans, even though the actual pain associated with bodily trauma remained largely absent. Throughout the war years, "white-robed heroes" (so named because of the robes worn by Japanese wounded soldiers during and after convalescence) were celebrated as national heroes and icons of "selfless sacrifice" (166). Pennington draws upon the work of Rosemarie Garland-Thomson and others to show how wartime Japanese culture attempted to defuse doubts about high casualty rates by downplaying the physical limitations associated with serious injury. Indeed, Pennington suggests that the "extraordinary treatment of disabled veterans in mass culture" played an important role in cementing public support for the war effort, even in its darkest hours (193).

We might imagine, then, the surprise and outrage felt by disabled veterans when they were increasingly marginalized in Japan's postwar "loser's narrative" (9). Eager to stamp out the last vestiges of Japanese militarism, the occupying Supreme Commander for Allied Powers (SCAP) dismantled the veterans' assistance system and stripped disabled veterans of their military pensions. SCAP insisted that disabled veterans did not deserve special consideration based upon their military service. They were, instead, lumped into a larger population of "war sufferers," their stories of hardship quickly eclipsed by those of bereaved families and other civilian casualties (197). In this respect, Pennington opines, disabled Japanese veterans of World War II were "doubly casualties of history"—first injured in a failed war and then forgotten by a nation eager to exorcise the ghosts of its martial past (16). It is a historical lesson that the latest generation of US disabled veterans should take to heart: nations tend to "support the troops" when it is convenient. The "white-robed hero" one day might be penniless in the streets the next.

Casualties of History ends, somewhat abruptly, in the early 1950s, and I could not help but wonder what happened next. What happened to the 60,000-member Japan Disabled Veterans Association, which Pennington tantalizingly mentions in the book's introduction (14)? Were disabled veterans left behind during the vaunted Japanese "economic miracle" of the 1960s-1980s? Did they remain "forgotten men" until the revival of interest in disabled veterans in the early 2000s? And to what extent did changing ideas about gender and sexuality shape responses to disabled veterans in the postwar years? Perhaps Pennington is already at work on a follow-up that addresses such questions. For now, though, we should appreciate the fine work that he has accomplished. Meticulously researched and thoughtfully conceived, Casualties of History is a premier work of disability history—one that deserves to be read by students and teachers alike.

References

Cohen, D. (2001). The War Come Home: Disabled Veterans in Britain and Germany, 1914-1939. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Linker, B. (2011). War's Waste: Rehabilitation in World War I America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Статья в англоязычной вики - это не плохо

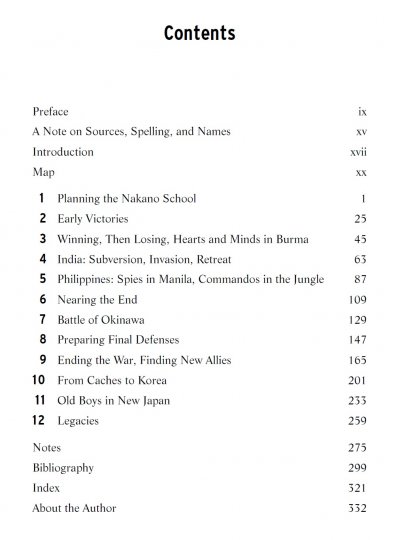

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nakano_School

Но 352-х страничное исследование Стивена Меркадо (бывшего аналитика ЦРУ, специализировавшегося на Азии) - много лучше

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nakano_School

Но 352-х страничное исследование Стивена Меркадо (бывшего аналитика ЦРУ, специализировавшегося на Азии) - много лучше

Вложения

Любопытный перевод рукописи контр-адмирала Томиока Садатоси, бывшего начальника Оперативного отдела Генерального штаба флота Японии.

http://www.rumvi.com/products/ebook...d-38ec34f82a99/preview/preview.html#TOC_ERTAE

http://www.rumvi.com/products/ebook...d-38ec34f82a99/preview/preview.html#TOC_ERTAE

Из оригинальной аннотации.

Труд Хани Горо «История японского народа» интересен для читатели во многих отношениях. В Японии вышло немало общих трудов по истории страны с древнейших времен и до наших дней. В большинстве это многотомные труды коллектива ученых, но некоторые из них написаны одним автором (Нэдзу Масаси, Идзу Киме и др.). Авторы этих изданий, желая подчеркнуть существенное отличие своих трудов от старых работ японских авторов, обычно именуют эти труды следующим образом: «Новая работа по истории Японии» или «История Японии в новом освещении» и т. д. В этих новых трудах значительно больше места, чем в прежних, отводится социально-экономическому анализу, роли народных масс, крестьянским и городским восстаниям, рабочему движению; меньше пишут в этих работах о правителях из императорской династии или династий сегунов (военно-феодальные правители Японии в XII–XIX веках), что составляло основное содержание традиционной японской историографии до 1945 года.Однако, насколько нам известно, не только до 1945 года, как об этом пишет Хани Горо в предисловии к своей книге, но и после 1945 года ни один из японских авторов не давал своей книге такого названия, какое дал Хани Горо, — «История японского народа». Это заглавие, а также предисловие автора показывают, что Хани Горо поставил своей целью полностью отойти от традиционной официозной японской историографии и противопоставить истории правителей и правящего класса историю народа, подлинного творца истории.Небольшие размеры труда Хани Горо и популярная форма изложения лишили автора возможности с одинаковой тщательностью и подробностью осветить все разделы почти двухтысячелетней истории японского народа. В книге есть некоторые пробелы, толкование некоторых важнейших переломных событий японской истории не вполне удовлетворит читателя. Но при всех этих недочетах, на которых мы остановимся подробнее дальше, сама идея — воссоздание истории народа, а неправящих классов, — новизна этой идеи для японской исторической науки и в целом ее умелое осуществление заставляют считать труд Хани Горо заслуживающим внимания читателя.

Что не страница, то гимн "японскому трудовому народу" и повсюду "крепостной гнет и эксплуатация"

Труд Хани Горо «История японского народа» интересен для читатели во многих отношениях. В Японии вышло немало общих трудов по истории страны с древнейших времен и до наших дней. В большинстве это многотомные труды коллектива ученых, но некоторые из них написаны одним автором (Нэдзу Масаси, Идзу Киме и др.). Авторы этих изданий, желая подчеркнуть существенное отличие своих трудов от старых работ японских авторов, обычно именуют эти труды следующим образом: «Новая работа по истории Японии» или «История Японии в новом освещении» и т. д. В этих новых трудах значительно больше места, чем в прежних, отводится социально-экономическому анализу, роли народных масс, крестьянским и городским восстаниям, рабочему движению; меньше пишут в этих работах о правителях из императорской династии или династий сегунов (военно-феодальные правители Японии в XII–XIX веках), что составляло основное содержание традиционной японской историографии до 1945 года.Однако, насколько нам известно, не только до 1945 года, как об этом пишет Хани Горо в предисловии к своей книге, но и после 1945 года ни один из японских авторов не давал своей книге такого названия, какое дал Хани Горо, — «История японского народа». Это заглавие, а также предисловие автора показывают, что Хани Горо поставил своей целью полностью отойти от традиционной официозной японской историографии и противопоставить истории правителей и правящего класса историю народа, подлинного творца истории.Небольшие размеры труда Хани Горо и популярная форма изложения лишили автора возможности с одинаковой тщательностью и подробностью осветить все разделы почти двухтысячелетней истории японского народа. В книге есть некоторые пробелы, толкование некоторых важнейших переломных событий японской истории не вполне удовлетворит читателя. Но при всех этих недочетах, на которых мы остановимся подробнее дальше, сама идея — воссоздание истории народа, а неправящих классов, — новизна этой идеи для японской исторической науки и в целом ее умелое осуществление заставляют считать труд Хани Горо заслуживающим внимания читателя.

Что не страница, то гимн "японскому трудовому народу" и повсюду "крепостной гнет и эксплуатация"

Стас Шимбу

Местный

Вложения

АЛЕКСЕЙ С.П.Б.

Местный

Несколько книг по Императорскому флоту на русском языке, на иностранных их вообще море.....