Вы используете устаревший браузер. Этот и другие сайты могут отображаться в нём некорректно.

Вам необходимо обновить браузер или попробовать использовать другой.

Вам необходимо обновить браузер или попробовать использовать другой.

Navy Cross type II или type III?

- Автор темы Igor Ostapenko

- Дата начала

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

замечательная группа наград с NX второго типа продавалась у Барри

https://www.emedals.com/north-ameri...-theodore-smith-uss-falcon-uss-squalus-rescue

https://www.emedals.com/north-ameri...-theodore-smith-uss-falcon-uss-squalus-rescue

Вложения

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

United States. A Navy Cross to Theodore Smith, USS Falcon, USS Squalus Rescue

A Navy Cross Group of Six, to Boatswain's Mate Second Class Theodore Preston Smith, USS Falcon, for the Rescue of Survivors from the submarine USS Squalus; Navy Cross (1940's style in blackened bronze, 37.3 mm (w) x 45.7 mm (h) inclusive of its ball suspension, original ribbon with brooch pinback); Navy Good Conduct Medal, 4 Clasps - 1937, 1941, FOURTH AWARD, FIFTH AWARD (bronze, engraved "THEODORE PRESTON SMITH 1932" on the reverse, 32.5 mm, frayed original ribbon with brooch pinback, reverse mounted); American Defense Service Medal, 1 Clasp - FLEET (bronze, 32.2 mm, original ribbon with brooch pinback); American Campaign Medal (bronze, 32 mm, original ribbon with brooch pinback); Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (bronze, 32 mm, original ribbon with brooch pinback); and World War II Campaign Medal (bronze, 36.2 mm, original ribbon with brooch pinback). Accompanied by his two Identification Tags (Dog Tags) (aluminum, stamped "SMITH / THEODORE P. / 243-29-31 / T-7-44-B / USN", 38.3 mm (w) x 32 mm (h) each, on a full-length neck chain); his Pearl Harbor Navy Yard Ship Repair Unit Badge (two voided panels, one with a black and white photo of Smith, the other with a identification panel inscribed "NAVY YARD - PEARL HARBOR / SHIP REPAIR UNIT / SMITH, T.P.", each panel under a celluloid shield within a silvered magnetic frame, 38.5 mm (w) x 58.2 mm (h), horizontal pinback, exhibiting surface rust on the frame); United States Navy Cap Badge (two-piece construction, silver "U.S.N" affixed to a bronze gilt fouled anchor base, 30.5 mm (w) x 44.8 mm (h), vertical pinback); and a Chief M.A.A. N.O.B. Badge (metal plate stamped "CHIEF / M.A.A. / N.O.B." affixed to a six-sided copper star base, 67 mm (w) x 77.5 mm (h), horizontal pinback). Light contact, near extremely fine.

Footnote: Boatswain's Mate Second Class Theodore Preston Smith was a member of the crew aboard the Lapwing-class minesweeper USS Falcon (AM-28/ASR-2), when he was awarded the Navy Cross in January 1940 for his part in the rescue of the survivors of the Sargo-class submarine USS Squalus (SS-192), which sank in 243 feet of water off Portsmouth, New Hampshire on May 23, 1939. The keel of the USS Squalus had been laid on October 18, 1937 by the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine and was launched on September 14, 1938. The 310-foot vessel displaced 2,350 tons when submerged and was armed with eight 21-inch torpedo tubes, a 3-inch deck gun, and two .50-caliber machine guns, designed to travel at a speed of eight knots when submerged. On May 12, 1939, following a yard overhaul, USS Squalus began a series of test dives off Portsmouth, New Hampshire under its captain, Lieutenant Oliver F. Naquin. After successfully completing eighteen eventless dives, she slipped beneath the storm-tossed surface of the Atlantic during a nineteenth sea trial on May 23rd. Minutes into the maneuver, she began flooding uncontrollably and went down again off the Isles of Shoals at 42°53′N 70°37′W, trapping 59 men (56 sailors and 3 civilians) on board. Failure of the main induction valve caused the flooding of the aft torpedo room, both engine rooms, and the crew's quarters, drowning 26 men (24 sailors and 2 civilians) immediately. Quick action by the remaining crew of 33 (32 sailors and 1 civilian) prevented the other compartments from flooding. Squalus bottomed in 243 ft (74 m) of water. To signal their distress, they sent up a marker buoy equipped with a telephone cable, and released red smoke bombs to the surface. Half a dozen Navy and Coast Guard vessels rushed to the scene. USS Sculpin (SS 191) was directed to search the Squalus’ dive area for signs of her sister submarine. An alert lookout spotted one of the smoke bombs released by Squalus and reported the sighting to the Navy Yard. While the Sculpin remained on scene, the Navy dispatched its Washington-based Experimental Diving Unit. After sighting the marker buoy, the Sculpin’s commander managed to speak with Naquin and confirm that there were survivors, even discussing rescue options before the communications cable parted. Now cut off from the world above, Squalus‘ survivors spent a cold night trapped inside their submarine, beginning to suffer ill effects from chlorine gas leaking from the battery compartment. No submarine rescue had ever succeeded beyond 20 feet of water. The Navy team had to use new methods that had existed only in theory before that day. They encountered problems that forced them to make decisions on the fly, each with life-or-death consequences. Divers from the submarine rescue ship USS Falcon began rescue operations under the direction of the salvage and rescue expert Lieutenant Commander Charles B. "Swede" Momsen, using the new McCann Rescue Chamber, a modified diving bell invented by Commander Charles B. Momsen and improved by Lieutenant Commander Allan Rockwell McCann. The device, manned by courageous deep-sea divers, made it possible to reach the crew.

The Senior Medical Officer for the operations was Dr. Charles Wesley Shilling. Overseen by researcher Albert R. Behnke, the divers used recently developed heliox diving schedules and successfully avoided the cognitive impairment symptoms associated with such deep dives, thereby confirming Behnke's theory of nitrogen narcosis. In three trips, the rescue chamber brought 26 men to the surface. After serious difficulty with tangled cables, the fourth trip finally rescued the last seven survivors in the dark hours before midnight on May 24th, thirty-nine hours after the sinking. The divers were able to rescue all 33 surviving crew members from the sunken submarine. Divers made a fifth, especially dangerous descent to confirm that there were no survivors in the aft torpedo room compartment. All this was accomplished while the world watching intently, captivated by the fate of the trapped men whose plight had been broadcast around the world at telegraph speed. Whether the men could be rescued before their oxygen ran out depended on an unproved diving bell, the seamanship of the crews, courageous divers, a quick-thinking admiral, a visionary submarine commander and the vagaries of New England weather. Four enlisted divers, Chief Machinist's Mate William Badders, Chief Boatswain's Mate Orson L. Crandall, Chief Metalsmith James H. McDonald and Chief Torpedoman John Mihalowski, were awarded the Medal of Honor for their work during the rescue and subsequent salvage. Forty-six seaman received the Navy Cross for their efforts in the rescue, including Boatswain's Mate Second Class Theodore Preston Smith. One other man received the Distinguished Service Medal. In the aftermath of the disaster, the U.S. Navy authorities felt it important to raise the USS Squalus, as she incorporated a succession of new design features. With a thorough investigation of why she sank, more confidence could be placed in the new construction, or alteration of existing designs could be undertaken when cheapest and most efficient to do so. The salvage of Squalus was commanded by Rear Admiral Cyrus W. Cole, Commander of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, who supervised salvage officer Lieutenant Floyd A. Tusler from the Construction Corps. Tusler's plan was to lift the submarine in three stages, to prevent it from rising too quickly, out of control, with one end up, in which case there would be a high likelihood of it sinking again.

For fifty days, divers worked to pass cables underneath the submarine and attach pontoons for buoyancy. On July 13, 1939, the stern was raised successfully, but when the men attempted to free the bow from the hard blue clay, the vessel began to rise far too quickly, slipping its cables. Ascending vertically, the submarine broke the surface, and 30 feet (10 m) of the bow reached into the air for not more than ten seconds before she sank once again all the way to the bottom. Momsen said of the mishap, "pontoons were smashed, hoses cut and I might add, hearts were broken." After twenty more days of preparation, with a radically redesigned pontoon and cable arrangement, the next lift was successful, as were two further operations. Squalus was towed into Portsmouth on September 13th, and decommissioned on November 15th. The submarine was renamed USS Sailfish and re-commissioned on February 9, 1940. With her new name, she was in port at Cavite Navy Yard in the Philippines when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Fighting from the very first day of the war, Sailfish would complete twelve war patrols and sink more than 45,000 tons of enemy shipping. On Dec. 3, 1944, during repeated torpedo attacks in a furious storm, USS Sailfish sank the Japanese escort carrier Chuyo. In a master stroke of irony, 20 of the 21 American prisoners aboard the enemy carrier died in the attack, all of which were from the submarine USS Sculpin, the same USS Sculpin that had help locate and raise USS Squalus (now USS Sailfish). The Navy would award USS Sailfish nine battle stars for action during the Second World War.

A Navy Cross Group of Six, to Boatswain's Mate Second Class Theodore Preston Smith, USS Falcon, for the Rescue of Survivors from the submarine USS Squalus; Navy Cross (1940's style in blackened bronze, 37.3 mm (w) x 45.7 mm (h) inclusive of its ball suspension, original ribbon with brooch pinback); Navy Good Conduct Medal, 4 Clasps - 1937, 1941, FOURTH AWARD, FIFTH AWARD (bronze, engraved "THEODORE PRESTON SMITH 1932" on the reverse, 32.5 mm, frayed original ribbon with brooch pinback, reverse mounted); American Defense Service Medal, 1 Clasp - FLEET (bronze, 32.2 mm, original ribbon with brooch pinback); American Campaign Medal (bronze, 32 mm, original ribbon with brooch pinback); Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal (bronze, 32 mm, original ribbon with brooch pinback); and World War II Campaign Medal (bronze, 36.2 mm, original ribbon with brooch pinback). Accompanied by his two Identification Tags (Dog Tags) (aluminum, stamped "SMITH / THEODORE P. / 243-29-31 / T-7-44-B / USN", 38.3 mm (w) x 32 mm (h) each, on a full-length neck chain); his Pearl Harbor Navy Yard Ship Repair Unit Badge (two voided panels, one with a black and white photo of Smith, the other with a identification panel inscribed "NAVY YARD - PEARL HARBOR / SHIP REPAIR UNIT / SMITH, T.P.", each panel under a celluloid shield within a silvered magnetic frame, 38.5 mm (w) x 58.2 mm (h), horizontal pinback, exhibiting surface rust on the frame); United States Navy Cap Badge (two-piece construction, silver "U.S.N" affixed to a bronze gilt fouled anchor base, 30.5 mm (w) x 44.8 mm (h), vertical pinback); and a Chief M.A.A. N.O.B. Badge (metal plate stamped "CHIEF / M.A.A. / N.O.B." affixed to a six-sided copper star base, 67 mm (w) x 77.5 mm (h), horizontal pinback). Light contact, near extremely fine.

Footnote: Boatswain's Mate Second Class Theodore Preston Smith was a member of the crew aboard the Lapwing-class minesweeper USS Falcon (AM-28/ASR-2), when he was awarded the Navy Cross in January 1940 for his part in the rescue of the survivors of the Sargo-class submarine USS Squalus (SS-192), which sank in 243 feet of water off Portsmouth, New Hampshire on May 23, 1939. The keel of the USS Squalus had been laid on October 18, 1937 by the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine and was launched on September 14, 1938. The 310-foot vessel displaced 2,350 tons when submerged and was armed with eight 21-inch torpedo tubes, a 3-inch deck gun, and two .50-caliber machine guns, designed to travel at a speed of eight knots when submerged. On May 12, 1939, following a yard overhaul, USS Squalus began a series of test dives off Portsmouth, New Hampshire under its captain, Lieutenant Oliver F. Naquin. After successfully completing eighteen eventless dives, she slipped beneath the storm-tossed surface of the Atlantic during a nineteenth sea trial on May 23rd. Minutes into the maneuver, she began flooding uncontrollably and went down again off the Isles of Shoals at 42°53′N 70°37′W, trapping 59 men (56 sailors and 3 civilians) on board. Failure of the main induction valve caused the flooding of the aft torpedo room, both engine rooms, and the crew's quarters, drowning 26 men (24 sailors and 2 civilians) immediately. Quick action by the remaining crew of 33 (32 sailors and 1 civilian) prevented the other compartments from flooding. Squalus bottomed in 243 ft (74 m) of water. To signal their distress, they sent up a marker buoy equipped with a telephone cable, and released red smoke bombs to the surface. Half a dozen Navy and Coast Guard vessels rushed to the scene. USS Sculpin (SS 191) was directed to search the Squalus’ dive area for signs of her sister submarine. An alert lookout spotted one of the smoke bombs released by Squalus and reported the sighting to the Navy Yard. While the Sculpin remained on scene, the Navy dispatched its Washington-based Experimental Diving Unit. After sighting the marker buoy, the Sculpin’s commander managed to speak with Naquin and confirm that there were survivors, even discussing rescue options before the communications cable parted. Now cut off from the world above, Squalus‘ survivors spent a cold night trapped inside their submarine, beginning to suffer ill effects from chlorine gas leaking from the battery compartment. No submarine rescue had ever succeeded beyond 20 feet of water. The Navy team had to use new methods that had existed only in theory before that day. They encountered problems that forced them to make decisions on the fly, each with life-or-death consequences. Divers from the submarine rescue ship USS Falcon began rescue operations under the direction of the salvage and rescue expert Lieutenant Commander Charles B. "Swede" Momsen, using the new McCann Rescue Chamber, a modified diving bell invented by Commander Charles B. Momsen and improved by Lieutenant Commander Allan Rockwell McCann. The device, manned by courageous deep-sea divers, made it possible to reach the crew.

The Senior Medical Officer for the operations was Dr. Charles Wesley Shilling. Overseen by researcher Albert R. Behnke, the divers used recently developed heliox diving schedules and successfully avoided the cognitive impairment symptoms associated with such deep dives, thereby confirming Behnke's theory of nitrogen narcosis. In three trips, the rescue chamber brought 26 men to the surface. After serious difficulty with tangled cables, the fourth trip finally rescued the last seven survivors in the dark hours before midnight on May 24th, thirty-nine hours after the sinking. The divers were able to rescue all 33 surviving crew members from the sunken submarine. Divers made a fifth, especially dangerous descent to confirm that there were no survivors in the aft torpedo room compartment. All this was accomplished while the world watching intently, captivated by the fate of the trapped men whose plight had been broadcast around the world at telegraph speed. Whether the men could be rescued before their oxygen ran out depended on an unproved diving bell, the seamanship of the crews, courageous divers, a quick-thinking admiral, a visionary submarine commander and the vagaries of New England weather. Four enlisted divers, Chief Machinist's Mate William Badders, Chief Boatswain's Mate Orson L. Crandall, Chief Metalsmith James H. McDonald and Chief Torpedoman John Mihalowski, were awarded the Medal of Honor for their work during the rescue and subsequent salvage. Forty-six seaman received the Navy Cross for their efforts in the rescue, including Boatswain's Mate Second Class Theodore Preston Smith. One other man received the Distinguished Service Medal. In the aftermath of the disaster, the U.S. Navy authorities felt it important to raise the USS Squalus, as she incorporated a succession of new design features. With a thorough investigation of why she sank, more confidence could be placed in the new construction, or alteration of existing designs could be undertaken when cheapest and most efficient to do so. The salvage of Squalus was commanded by Rear Admiral Cyrus W. Cole, Commander of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, who supervised salvage officer Lieutenant Floyd A. Tusler from the Construction Corps. Tusler's plan was to lift the submarine in three stages, to prevent it from rising too quickly, out of control, with one end up, in which case there would be a high likelihood of it sinking again.

For fifty days, divers worked to pass cables underneath the submarine and attach pontoons for buoyancy. On July 13, 1939, the stern was raised successfully, but when the men attempted to free the bow from the hard blue clay, the vessel began to rise far too quickly, slipping its cables. Ascending vertically, the submarine broke the surface, and 30 feet (10 m) of the bow reached into the air for not more than ten seconds before she sank once again all the way to the bottom. Momsen said of the mishap, "pontoons were smashed, hoses cut and I might add, hearts were broken." After twenty more days of preparation, with a radically redesigned pontoon and cable arrangement, the next lift was successful, as were two further operations. Squalus was towed into Portsmouth on September 13th, and decommissioned on November 15th. The submarine was renamed USS Sailfish and re-commissioned on February 9, 1940. With her new name, she was in port at Cavite Navy Yard in the Philippines when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Fighting from the very first day of the war, Sailfish would complete twelve war patrols and sink more than 45,000 tons of enemy shipping. On Dec. 3, 1944, during repeated torpedo attacks in a furious storm, USS Sailfish sank the Japanese escort carrier Chuyo. In a master stroke of irony, 20 of the 21 American prisoners aboard the enemy carrier died in the attack, all of which were from the submarine USS Sculpin, the same USS Sculpin that had help locate and raise USS Squalus (now USS Sailfish). The Navy would award USS Sailfish nine battle stars for action during the Second World War.

Вложения

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

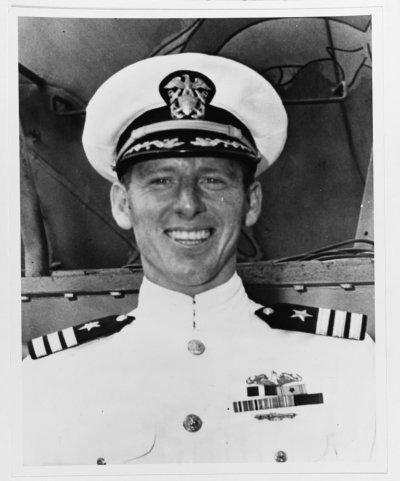

известный повар, получивший Navy Cross весной 1942 года, его Куба Гудинг младший сыграл в фильме "Перл Харбор"

его именем назвали новое судно в составе ВМФ

Вложения

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

в продаже крест второго типа

Вложения

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

только что-то слабо верится в четыре звёздочки, но это и не важно

Хорошие изображения редкого предмета !

Если бы уже на затарился , то обязательно бы взял ...

Хорошие изображения редкого предмета !

Если бы уже на затарился , то обязательно бы взял ...

Вложения

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

Igor Ostapenko

Участник АК

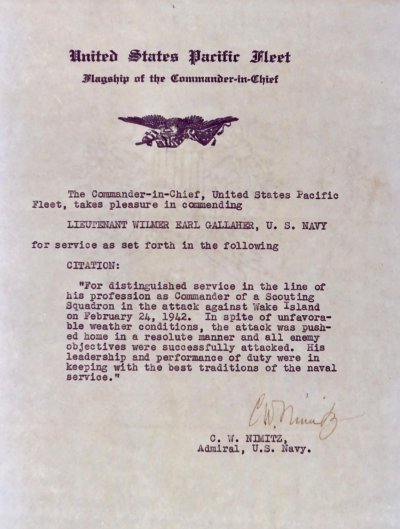

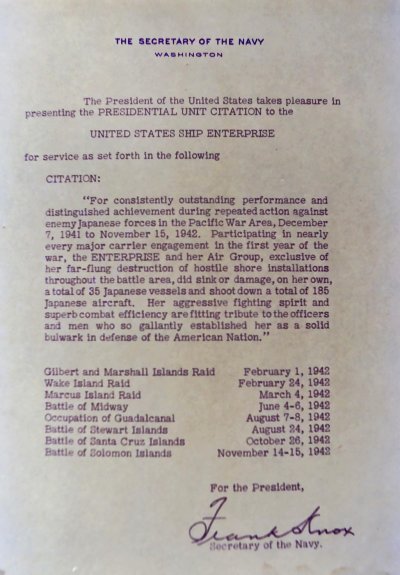

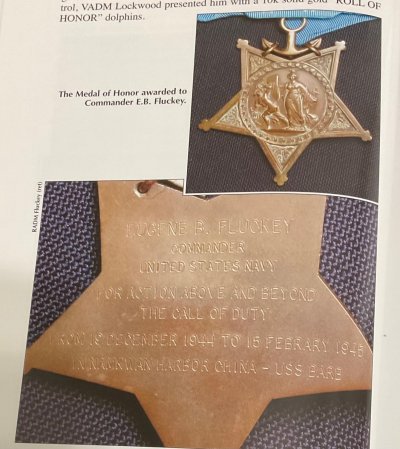

Medal of Honor group to Adm. Eugene B. Fluckey, commanding officer of the USS Barb during WWII......

Вложения

-

IMG_1003.jpeg153.9 KB · Просмотры: 4

IMG_1003.jpeg153.9 KB · Просмотры: 4 -

IMG_0994.jpeg334.7 KB · Просмотры: 4

IMG_0994.jpeg334.7 KB · Просмотры: 4 -

IMG_0992.jpeg303 KB · Просмотры: 4

IMG_0992.jpeg303 KB · Просмотры: 4 -

IMG_0993.jpeg211.1 KB · Просмотры: 4

IMG_0993.jpeg211.1 KB · Просмотры: 4 -

IMG_0995.jpeg294.1 KB · Просмотры: 4

IMG_0995.jpeg294.1 KB · Просмотры: 4 -

IMG_0996.jpeg317.5 KB · Просмотры: 4

IMG_0996.jpeg317.5 KB · Просмотры: 4 -

IMG_0997.jpeg148.4 KB · Просмотры: 5

IMG_0997.jpeg148.4 KB · Просмотры: 5 -

IMG_0998.jpeg635.7 KB · Просмотры: 5

IMG_0998.jpeg635.7 KB · Просмотры: 5 -

IMG_0999.jpeg624.2 KB · Просмотры: 5

IMG_0999.jpeg624.2 KB · Просмотры: 5