Вы используете устаревший браузер. Этот и другие сайты могут отображаться в нём некорректно.

Вам необходимо обновить браузер или попробовать использовать другой.

Вам необходимо обновить браузер или попробовать использовать другой.

Немецкие военнопленные в японских лагерях первой мировой войны

- Автор темы Спирька Шпандырь

- Дата начала

Русская версия статьи Сэто Такэхико

Япония в Первой мировой войне: немецкие военнопленные в японских лагерях

английская версия https://www.nippon.com/en/in-depth/a03303/

русская версия https://www.nippon.com/ru/in-depth/a03303/

Во время Первой мировой войны в разных регионах Японии содержалось около 4700 немецких военнопленных. Исторические документы показывают, что японское правительство тщательно соблюдало международное законодательство.

В 2014 году исполнилось 100 лет с момента начала Первой мировой войны. В Японии многие считают её европейской войной и редко о ней говорят – возможно, оттого, что события Второй мировой гораздо сильнее отпечатались в памяти. Хотя они обе называются «мировыми», но между ними есть огромные различия. В Первой мировой Япония участвовала в качестве одного из Союзников, однако реальные боевые действия Японии практически исчерпывались столкновением с немецкими войсками – осадой Циндао на Шаньдунском полуострове, которая продолжалась всего каких-то полтора месяца. В результате этой осады около 4700 пленных немецких солдат оказалось в 16 различных местах в разных регионах Японии, и они там содержались на протяжении более пяти лет. Об этом эпизоде войны уже никто не помнит.

Соблюдение норм международного права в лагерях для военнопленных

Здесь мы употребляем выражение «немецкие военнопленные», хотя в действительности среди них были и австрийцы, и венгры, и чехи, и поляки, и представители других национальностей, – но поскольку подавляющее большинство пленных составляли немцы, говоря о них в общем мы для простоты называем их «немецкими военнопленными».

В Японии при обращении с военнопленными старались соблюдать международные нормы. 18 октября 1907 года была подписана Гаагская конвенция, а 13 января 1912 года её опубликовали в Японии. Одним из документов была Конвенция о законах и обычаях сухопутной войны. В статье 4 главы 2 «О военнопленных» говорится, что с военнопленными «надлежит обращаться человеколюбиво». Япония, за десять лет до этого одержавшая победу в войне с Россией(*1), стремилась к тому, чтобы Европа и США признали её цивилизованной страной, и поэтому в лагерях ни в коем случае не допускалось насилие над военнопленными либо принуждение к работам.

15 ноября 1915 года в лагере Курумэ в преф. Фукуока начальник лагеря Масаки Дзиндзабуро нанёс побои пленным офицерам. По случаю восшествия на трон императора Тайсё пленным выдали по бутылке пива и по два яблока, но двое офицеров отказались принять подарок, сославшись на то, что их страна находится в состоянии войны с Японией. Разъярённый Масаки отхлестал их по щекам. Поскольку Гаагская конвенция запрещала жестокое обращение с военнопленными, те были крайне возмущены поступком Масаки, и дело дошло до того, что они потребовали встречи с представителем американского посольства (США тогда ещё не вступили в войну). Масаки уволили с должности начальника лагеря. Наверное, следует считать этот инцидент единичным случаем. Кое-где иногда бывали небольшие недоразумения между служащими лагерей и военнопленными, но случаев, которые можно было бы назвать жестоким обращением, практически не было.

Свободные порядки в лагерях

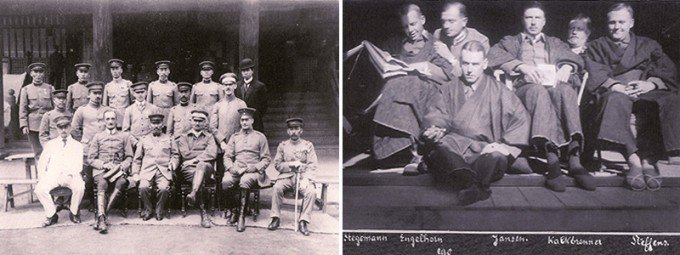

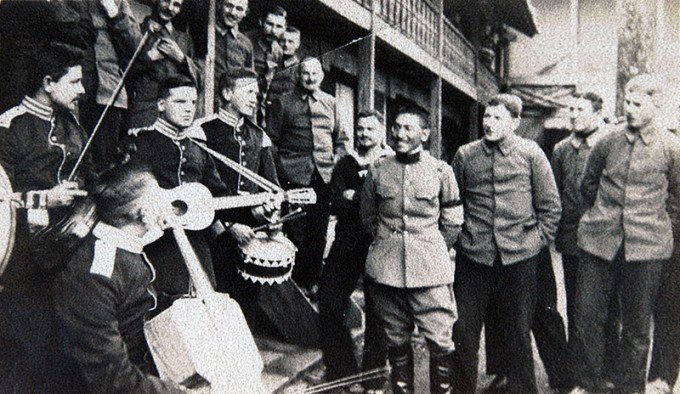

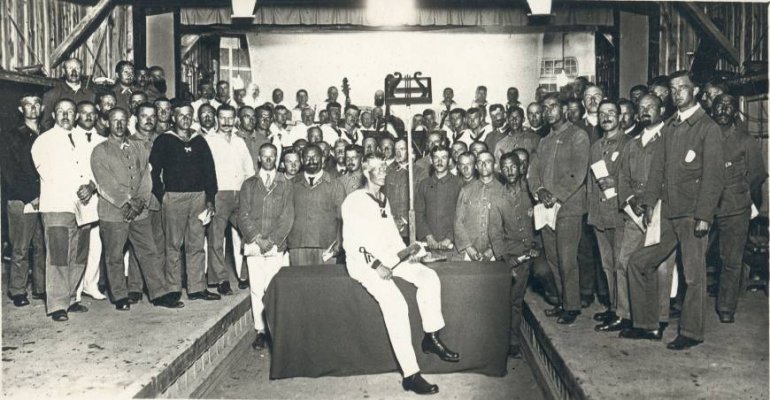

Фотография 1 (предоставлена Немецким домом г. Наруто), фотография 2 (предоставлена Освальдом Хассельманном)

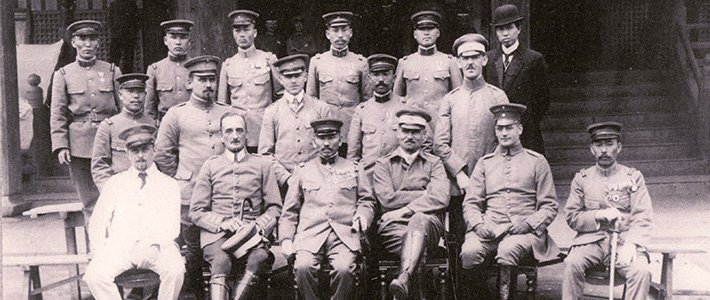

Фотография 1 сделана в начале апреля 1916 года. Служащие лагеря Маругамэ в преф. Кагава снялись на память вместе с пленными офицерами. Вероятно, фотография сделана по случаю ухода с должности начальника лагеря полковника Исии Ясиро. Полковник Исии в центре сидит довольно скованно – возможно, из-за болезни, а немецкие офицеры приняли непринуждённые позы, и не похожи на пленных. По фотографии видно, как в Японии обращались с военнопленными.

На фотографии 2 мы видим военнопленных в лагере в Нагое. Неизвестно, когда сделан снимок, но по одежде можно предположить, что снимали зимой. Пленные выбрали хорошо освещённое место в комнате и расположились, как кому удобно. Они не выглядят как люди, страдающие от слишком строгих порядков в лагере.

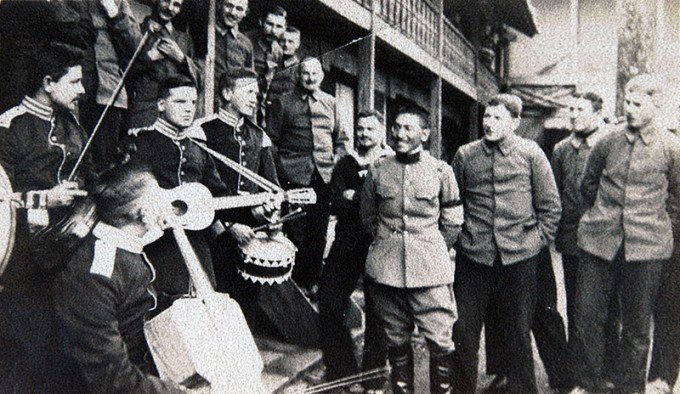

Фотография 3 (Архив Комитета образования г. Курумэ)

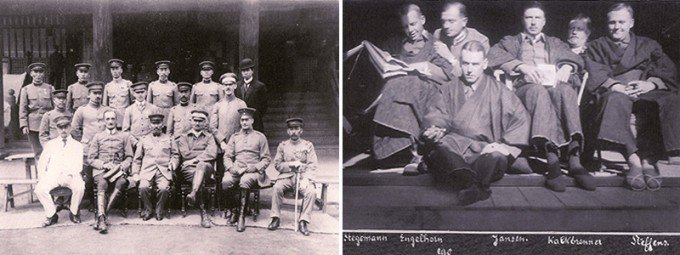

Фотография 3 снята в лагере для военнопленных города Курумэ преф. Фукуока 27 января 1915 г. В этот день военнопленные праздновали день рождения императора Вильгельма II. На этой фотографии лейтенант Ямамото Сигэру ведёт непринуждённую весёлую беседу с немецкими пленными. Он в своё время учился в военной академии в Германии и бегло говорил по-немецки. Из дневников одного из бывших пленных известно, что Ямамото, чтобы улучшить знание немецкого языка, давал уроки японского одному из немцев, а тот учил его немецкому. Вообще-то существует множество фотографий, где запечатлены вместе немецкие и японские офицеры, но улыбающиеся лица встречаются крайне редко.

Фотография 1 (предоставлена Немецким домом г. Наруто), фотография 2 (предоставлена Освальдом Хассельманном)

Фотография 1 сделана в начале апреля 1916 года. Служащие лагеря Маругамэ в преф. Кагава снялись на память вместе с пленными офицерами. Вероятно, фотография сделана по случаю ухода с должности начальника лагеря полковника Исии Ясиро. Полковник Исии в центре сидит довольно скованно – возможно, из-за болезни, а немецкие офицеры приняли непринуждённые позы, и не похожи на пленных. По фотографии видно, как в Японии обращались с военнопленными.

На фотографии 2 мы видим военнопленных в лагере в Нагое. Неизвестно, когда сделан снимок, но по одежде можно предположить, что снимали зимой. Пленные выбрали хорошо освещённое место в комнате и расположились, как кому удобно. Они не выглядят как люди, страдающие от слишком строгих порядков в лагере.

Фотография 3 (Архив Комитета образования г. Курумэ)

Фотография 3 снята в лагере для военнопленных города Курумэ преф. Фукуока 27 января 1915 г. В этот день военнопленные праздновали день рождения императора Вильгельма II. На этой фотографии лейтенант Ямамото Сигэру ведёт непринуждённую весёлую беседу с немецкими пленными. Он в своё время учился в военной академии в Германии и бегло говорил по-немецки. Из дневников одного из бывших пленных известно, что Ямамото, чтобы улучшить знание немецкого языка, давал уроки японского одному из немцев, а тот учил его немецкому. Вообще-то существует множество фотографий, где запечатлены вместе немецкие и японские офицеры, но улыбающиеся лица встречаются крайне редко.

Бесплатная почта и денежное довольствие

Я приведу три положения Гаагской конвенции, которые выглядят сегодня довольно необычно.

Статья 10. «Военнопленные могут быть освобождаемы на честное слово, если это разрешается законами их страны».

Сейчас правило об освобождении под честное слово выглядит удивительно, но во времена Первой мировой оно было зафиксировано в международных договорах. Вот пример присяги военнопленного из Палау, бывшей немецкой колонии, захваченной Японией в период военных действий против Германии:

«Я, нижеподписавшийся, искренне обещаю, что в течение нынешней войны ни при каких обстоятельствах не вступлю вновь в ряды вооружённых сил Германии. 3 год Тайсё (1914), месяц, день. Палау».

И в самой Японии также в начальный период войны несколько военнопленных были освобождены под честное слово. Когда 11 ноября 1918 года было заключено перемирие, многие военнопленные отличных от немцев национальностей, такие как французы из Эльзаса и Лотарингии, итальянцы, поляки, чехи, были освобождены под честное слово, а всего так освободили около 100 человек.

Статья 16. «Письма, переводы, денежные суммы, равно как и почтовые посылки, адресуемые военнопленным или ими отправляемые, освобождаются от всех почтовых сборов как в странах отправления и назначения, так и в промежуточных странах».

Количество дозволяющихся бесплатных почтовых отправлений различалось в зависимости от звания военнослужащего, а в среднем составляло в месяц 5 посылок для офицеров, 3 для унтер-офицеров, и 2 для рядовых. Возможна была не только международная пересылка, но и почтовое сообщение между лагерями. За пять лет существования лагерей для военнопленных всего было переслано более миллиона почтовых отправлений, учитывая и те, которые были присланы пленным с их родины. На самом деле исследования истории немецких военнопленных в Японии во времена Первой мировой начали коллекционеры писем и почтовых открыток военнопленных того времени.

Статья 17. «Военнопленные офицеры получают оклад, на который имеют право офицеры того же ранга страны, где они задержаны, под условием возмещения такового расхода их Правительством».

Сохранились записи рассказов Сайго Торатаро, начальника лагеря в Токио. Он говорил: «Месячная плата военнопленным составляла 183 йены для подполковников, 47 для лейтенантов, 40 для младших лейтенантов, 40 для прапорщиков, и 30 сэнов (0,3 йены) в день для унтер-офицеров и ниже. Эти расценки соответствовали плате в наших войсках… Эта плата была предназначена для сохранения достоинства военных и соответствовала правилам обращения с военнопленными. Далее, на эти деньги офицеры должны были обеспечивать себя едой, одеждой и жильём, а нижние чины обеспечивались едой и одеждой, и свою плату могли расходовать на лакомства и другие мелочи – мандарины, печенье, кофе, сигареты и прочие вещи, по желанию».

В перечне военных чинов, перечисленных Сайго, нет никого выше подполковников. Это объясняется тем, что в токийском лагере не было таких пленных. В официальных расчётах же плата составляла для флотских капитанов первого ранга 262 йены, капитанов второго ранга – 200 йен, третьего ранга – 137 йен, капитан-лейтенантов – 82 йены, лейтенантов – 55 йен, младших лейтенантов – 46 йен, а для армейских полковников – 240 йен, подполковников – 183 йены, майоров – 129 йен, капитанов – 75 йен, лейтенантов – 46 йен, и для младших лейтенантов – 42 йены.

Сравнивая по потребительским ценам, 200 йен того времени соответствуют примерно 1,6 млн йен (12 000 долларов США) сейчас. Заработная плата начинающего клерка в крупном банке тогда составляла около 40 йен, так что мы можем видеть, насколько хорошо платили старшему офицерскому составу.

(*1) ^ Прим. перев. – Для русскоязычных читателей следует упомянуть и о гуманном обращении с военнопленными в период Русско-японской войны (1904-1905). Через лагерь Мацуяма в преф. Эхимэ за весь период его существования прошло около 6000 российских солдат и офицеров. Им было позволено свободно передвигаться вне лагеря, они устраивали различные мероприятия, путешествовали по окрестностям, посещали термальные источники. С тех пор прошло более века, но учащиеся школы средней ступени Кацута регулярно посещают кладбище, где похоронено 98 скончавшихся в плену российских подданных, и ухаживают за их могилами.

Я приведу три положения Гаагской конвенции, которые выглядят сегодня довольно необычно.

Статья 10. «Военнопленные могут быть освобождаемы на честное слово, если это разрешается законами их страны».

Сейчас правило об освобождении под честное слово выглядит удивительно, но во времена Первой мировой оно было зафиксировано в международных договорах. Вот пример присяги военнопленного из Палау, бывшей немецкой колонии, захваченной Японией в период военных действий против Германии:

«Я, нижеподписавшийся, искренне обещаю, что в течение нынешней войны ни при каких обстоятельствах не вступлю вновь в ряды вооружённых сил Германии. 3 год Тайсё (1914), месяц, день. Палау».

И в самой Японии также в начальный период войны несколько военнопленных были освобождены под честное слово. Когда 11 ноября 1918 года было заключено перемирие, многие военнопленные отличных от немцев национальностей, такие как французы из Эльзаса и Лотарингии, итальянцы, поляки, чехи, были освобождены под честное слово, а всего так освободили около 100 человек.

Статья 16. «Письма, переводы, денежные суммы, равно как и почтовые посылки, адресуемые военнопленным или ими отправляемые, освобождаются от всех почтовых сборов как в странах отправления и назначения, так и в промежуточных странах».

Количество дозволяющихся бесплатных почтовых отправлений различалось в зависимости от звания военнослужащего, а в среднем составляло в месяц 5 посылок для офицеров, 3 для унтер-офицеров, и 2 для рядовых. Возможна была не только международная пересылка, но и почтовое сообщение между лагерями. За пять лет существования лагерей для военнопленных всего было переслано более миллиона почтовых отправлений, учитывая и те, которые были присланы пленным с их родины. На самом деле исследования истории немецких военнопленных в Японии во времена Первой мировой начали коллекционеры писем и почтовых открыток военнопленных того времени.

Статья 17. «Военнопленные офицеры получают оклад, на который имеют право офицеры того же ранга страны, где они задержаны, под условием возмещения такового расхода их Правительством».

Сохранились записи рассказов Сайго Торатаро, начальника лагеря в Токио. Он говорил: «Месячная плата военнопленным составляла 183 йены для подполковников, 47 для лейтенантов, 40 для младших лейтенантов, 40 для прапорщиков, и 30 сэнов (0,3 йены) в день для унтер-офицеров и ниже. Эти расценки соответствовали плате в наших войсках… Эта плата была предназначена для сохранения достоинства военных и соответствовала правилам обращения с военнопленными. Далее, на эти деньги офицеры должны были обеспечивать себя едой, одеждой и жильём, а нижние чины обеспечивались едой и одеждой, и свою плату могли расходовать на лакомства и другие мелочи – мандарины, печенье, кофе, сигареты и прочие вещи, по желанию».

В перечне военных чинов, перечисленных Сайго, нет никого выше подполковников. Это объясняется тем, что в токийском лагере не было таких пленных. В официальных расчётах же плата составляла для флотских капитанов первого ранга 262 йены, капитанов второго ранга – 200 йен, третьего ранга – 137 йен, капитан-лейтенантов – 82 йены, лейтенантов – 55 йен, младших лейтенантов – 46 йен, а для армейских полковников – 240 йен, подполковников – 183 йены, майоров – 129 йен, капитанов – 75 йен, лейтенантов – 46 йен, и для младших лейтенантов – 42 йены.

Сравнивая по потребительским ценам, 200 йен того времени соответствуют примерно 1,6 млн йен (12 000 долларов США) сейчас. Заработная плата начинающего клерка в крупном банке тогда составляла около 40 йен, так что мы можем видеть, насколько хорошо платили старшему офицерскому составу.

(*1) ^ Прим. перев. – Для русскоязычных читателей следует упомянуть и о гуманном обращении с военнопленными в период Русско-японской войны (1904-1905). Через лагерь Мацуяма в преф. Эхимэ за весь период его существования прошло около 6000 российских солдат и офицеров. Им было позволено свободно передвигаться вне лагеря, они устраивали различные мероприятия, путешествовали по окрестностям, посещали термальные источники. С тех пор прошло более века, но учащиеся школы средней ступени Кацута регулярно посещают кладбище, где похоронено 98 скончавшихся в плену российских подданных, и ухаживают за их могилами.

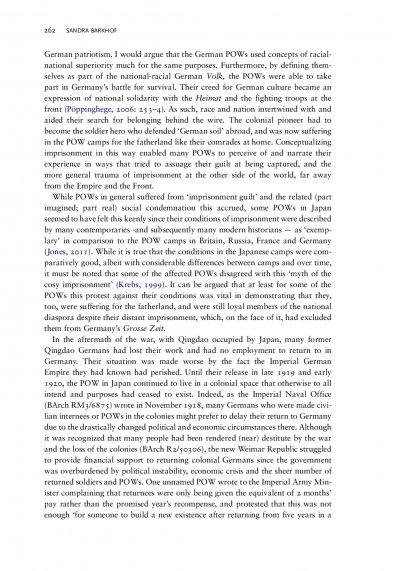

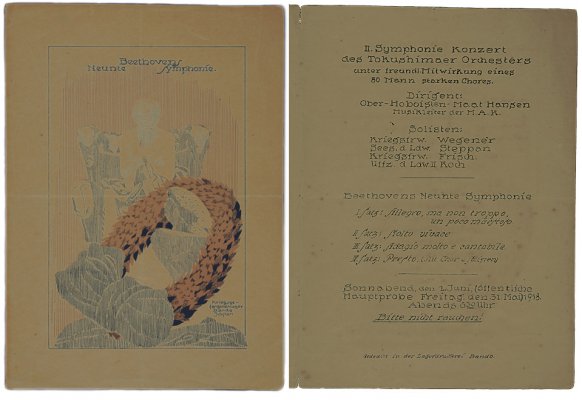

Profound performance: Prisoner of war Hermann Hansen (seated, center) conducted the Tokushima Orchestra and a choir made up of other POWs in a performance of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony that was held June 1, 1918, in Tokushima Prefecture. | NARUTO GERMAN HOUSE

From a POW camp to esteemed music halls nationwide: Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 marks 100 years in Japan

BY CHIHO IUCHI

It’s rare that a concert has so much impact that people still talk about it 100 years later. However, that’s certainly the case for a performance a century ago by some German prisoners of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in Tokushima Prefecture. It was the masterpiece’s first performance in a country that would later make it part of its year-end holiday tradition.

The story effectively starts after the siege of Tsingtao in 1914 during World War I, when Japan and Britain teamed up to boot Germany out of the colony it had established there. They were successful, and 4,700 POWs were brought to Japan, with some 1,000 being placed in the Bando camp in what is now the city of Naruto, Tokushima.

They were the lucky ones — or as lucky as you can get when you’re a prisoner.

“In the Bando POW camp, the prisoners were allowed to conduct various activities such as run shops, bars and restaurants; publish newspapers; build private lodges; and enjoy sports, art and music,” says Kiyoharu Mori, director of the Naruto German House. “It was partly thanks to the leadership of Col. Toyohisa Matsue, the head of the Bando camp, that the POWs were treated in such a humane and flexible manner.”

Born to an Aizu domain samurai family who fought against the Imperial Army around the time of the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Matsue experienced a good deal of hardship during his childhood, which is said to have given him a sense of what it meant to be defeated. He wasn’t without his critics, especially among his superiors, but that didn’t stop him from running Bando the way he wanted.

His light hand was also in keeping with local custom. People living in the area were taken aback by the decision to locate the 1,000 Germans at Bando — it was around twice the size of the town’s population. Eventually, they began to interact with them, referring to them as “Doitsu-san” (“Mr. German”).

“The townspeople had a long-held tradition of o-settai (hospitality and openness toward pilgrims), as nearby Ryozenji temple is the starting point of the Shikoku Pilgrimage,” Mori says, referring to the well-traveled route that takes in 88 different temples. “Even today, I’ll see friendly locals speaking with tourists from overseas who are walking the route.”

The German POWs, more than half of whom weren’t professional soldiers, also contributed to the community by teaching the locals skills from their regular jobs as engineers, craftsmen and artists. As part of cultural activities, more than 100 concerts were organized in the Bando camp. Two orchestras, two choirs and many smaller groups comprised of POWs performed songs, symphonies and other musical pieces.

The performance on June 1, 1918, of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 — known as “Daiku” (No. 9) to the Japanese — was one of those cultural activities. Conducted by POW Hermann Hansen, the 45-member Tokushima Orchestra and an 80-member choir performed the symphony from the first movement to the choral finale. Unfortunately, the concert was limited to those inside the camp, but word of it reached Yorisada Tokugawa, a renowned patron of Western classical music in Tokyo.

“According to his 1943 book ‘Waitei Gakuwa’ (‘My Stories on Music’), Japanese musicians were not yet able to perform the symphony in the 1910s” because their technical ability wasn’t high enough, says Sumiko Hasegawa, curator of The Naruto German House. “So Tokugawa visited the Bando camp in August 1918, where the POWs played the first movement again for him.” Tokugawa’s verdict was that the performance was “not bad,” and he was impressed by the level of passion these amateur musicians displayed.

The first performance of “Daiku” by Japanese musicians came in 1925 at what is now the Tokyo University of Fine Arts.

After the end of World War I, the Bando prisoners began leaving. All were gone by 1920 and, with the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the largely positive exchanges between Japanese and Germans were soon forgotten. It wasn’t until the 1960s, when those former POWs revisited Japan, that a relationship with the citizens of Naruto resumed. In 1972, the city established Naruto German House to preserve and display this unique cultural heritage.

“Thanks to academic research from the 1970s and onward, we’ve come to realize that the 1918 ‘Daiku’ concert was actually the first one in Asia and a historic event,” explains Mori, adding that it also became a point of pride among locals.

The story entered a new chapter with the opening of the Naruto Bunka Kaikan hall in 1982. “Daiku” was performed by the amateur Tokushima Symphony Orchestra and a 377-member choir mainly made up of Naruto citizens. Thanks to the efforts of those choir members, and in particular former Mayor Toshiaki Kamei, the concert has been held annually as “Naruto Daiku” on the first Sunday of June.

In the rest of the country, however, “Daiku” performances have become a year-end tradition. This is partly due to economic reasons — the piece’s popularity guarantees a healthy audience turnout even when performed by increasing ranks of amateur choirs. Today more than 100 concerts are held nationwide every December.

“With fast passages and hard-to-sing high notes, ‘Daiku’ is a difficult work for amateurs to sing,” says Toshihide Koroyasu, who teaches music at Naruto University of Education and used to be a member of the Bavarian Radio Choir in Germany. After returning to Japan, Koroyasu was invited to join Naruto’s “Daiku” as a soloist in 1992, and has coached the choir ever since.

In marking the 100th anniversary of the POW performance, this year the city of Naruto is hosting a special concert titled “Yomigaeru Daiku” on June 1 in which they hope to re-create the 1918 concert. The vocals will all be performed by men, in keeping with the makeup of the German POWs, with Koroyasu, a tenor, serving as soprano solo.

Then, the annual concert at Naruto Bunka Kaikan will be held for two days (June 2 and 3), bringing together some 1,200 choir members (600 singers for each concert) under the baton of Thomas Dorsch. The choir will comprise people from several countries — Japan, Germany, the United States and, the former battlefield of Tsingtao, China.

Hideyuki Fujinaga, a senior staff writer at the Tokushima Shimbun, has been covering the run-up to the centenary celebrations since 2016. He has interviewed more than 100 people connected to the Bando story in Japan and Germany, and has found a universality to the piece.

“I feel there is a link between the ‘All people shall become brothers’ message that Beethoven’s Ninth conveys and the history of Bando, where Germans and Japanese embraced diversity with a spirit of tolerance,” Fujinaga says. “I think that’s why people still feel a connection to ‘Daiku.'”

Источник: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/cultur...hony-no-9-marks-100-years-japan/#.W4UYUM4zapp

Любопытная история и фотоархив от внука одного из военнопленных - Марка Факница.

From Tsingtau - Remembering and Forgetting: Some Photographs from a Small Corner of the Great War,

by Mark Facknitz

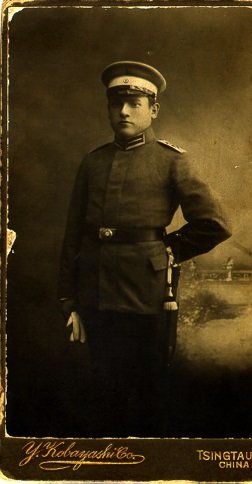

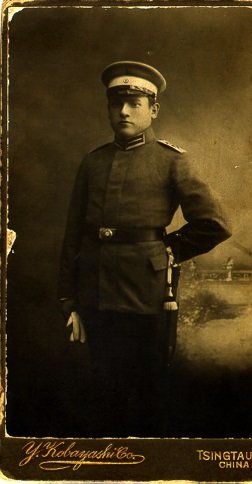

1. He was my grandfather, my Opa. Albert Karl Gustave Facknitz, born 12 September 1890, died December 1963. In October 1909 he began training in a marine unit, the naval infantry, joining the third Seebataillon, first Company; he was posted to Tsingtau (Qingdao) by February of the following year. He served for over a decade, including an eight month leave and redeployment to Cuxhaven in 1913. During that time he met Martha Zorn, one day my Oma. He returned to China, served as consular guard in Tientsin, then returned to Tsingtau for its fall, and was captured by the Japanese on 6 November 1914, the day before official surrender. After five years as a prisoner of war in Japan, Albert was repatriated to a Germany beset with the turmoil and shortages of the postwar period. He married Martha in November, 1920. The photograph, taken by Japanese photographer Y. Kobayashi in Tsingtau, was printed on heavy stock and sent back to Germany, he sent to his sweetheart in Pomerania, inscribed, “To remind you of me, your friend Albert.”

My grandfather was a private soldier, later a corporal, participating in the maintenance of Tsingtau, Germany’s most ambitious project as a late-comer to imperialism. As early as 1871, the German geographer, geologist, and world traveler Baron Ferdinand von Richtofen (uncle of the Red Baron), ended his overview of the wealth and potential of Shantung Province with this exhortation: “Although the rise of the Empire of China is likely to antagonize European interests in intellectual, material and industrial respects, still this rise will become urgent from the pressure of necessity, and taking this fact into consideration the various foreign powers will each have to secure for themselves the greatest possible advantage in the approaching era of China’s renascence” (Forsyth, 96). Sun-Yat-Sen, after a visit to Tsingtau with its spacious streets, running water and sewers, modern hospital and docks and rail terminus, offered the opinion that Tsingtau was a model for Chinese cities of the future.

From Tsingtau - Remembering and Forgetting: Some Photographs from a Small Corner of the Great War,

by Mark Facknitz

1. He was my grandfather, my Opa. Albert Karl Gustave Facknitz, born 12 September 1890, died December 1963. In October 1909 he began training in a marine unit, the naval infantry, joining the third Seebataillon, first Company; he was posted to Tsingtau (Qingdao) by February of the following year. He served for over a decade, including an eight month leave and redeployment to Cuxhaven in 1913. During that time he met Martha Zorn, one day my Oma. He returned to China, served as consular guard in Tientsin, then returned to Tsingtau for its fall, and was captured by the Japanese on 6 November 1914, the day before official surrender. After five years as a prisoner of war in Japan, Albert was repatriated to a Germany beset with the turmoil and shortages of the postwar period. He married Martha in November, 1920. The photograph, taken by Japanese photographer Y. Kobayashi in Tsingtau, was printed on heavy stock and sent back to Germany, he sent to his sweetheart in Pomerania, inscribed, “To remind you of me, your friend Albert.”

My grandfather was a private soldier, later a corporal, participating in the maintenance of Tsingtau, Germany’s most ambitious project as a late-comer to imperialism. As early as 1871, the German geographer, geologist, and world traveler Baron Ferdinand von Richtofen (uncle of the Red Baron), ended his overview of the wealth and potential of Shantung Province with this exhortation: “Although the rise of the Empire of China is likely to antagonize European interests in intellectual, material and industrial respects, still this rise will become urgent from the pressure of necessity, and taking this fact into consideration the various foreign powers will each have to secure for themselves the greatest possible advantage in the approaching era of China’s renascence” (Forsyth, 96). Sun-Yat-Sen, after a visit to Tsingtau with its spacious streets, running water and sewers, modern hospital and docks and rail terminus, offered the opinion that Tsingtau was a model for Chinese cities of the future.

Последнее редактирование модератором:

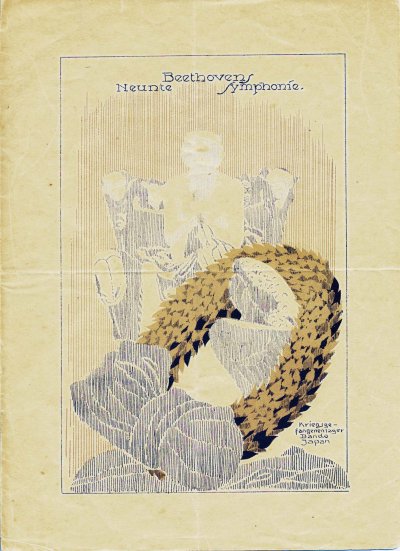

These are some of the photographs he brought back with him.

2. Among solid and stately administrative buildings, this cenotaph commemorated two German Catholic missionaries, Franz Xaver Nies and Richard Henle. They were killed by a gang from the Big Swords Society, 1 November 1897, in Zhiang Jia village in western Shantung. Nies and Henle, on All Soul’s Day, were visiting their colleague and fellow priest Georg Maria Stenz. Within two weeks of their death, Germany landed an occupying force at Kiaozhou Bay. Germany later compelled the Qing government to remove a regional governor, build three new Catholic churches, and pay a reparation of 3,000 taels. Later the singularity of the Juye incident, so-called, was blurred by the emergence of the broader and more coherent uprising Yihequan Movement, the Boxer Uprising, of 1899-1901. Simultaneously, Germany negotiated—exacted is perhaps a more nearly accurate term—the Kiautschou Bay Concession: a ninety-nine year lease of over two hundred square miles, which, while still belonging to China, were under the sovereignty of Germany. The agreement permitted construction of harbor facilities; a railroad connecting Shantung to Manchuria, and to the Tran-Siberian, and eventually Berlin; coal mining; and the planting of a modern German town.

2. Among solid and stately administrative buildings, this cenotaph commemorated two German Catholic missionaries, Franz Xaver Nies and Richard Henle. They were killed by a gang from the Big Swords Society, 1 November 1897, in Zhiang Jia village in western Shantung. Nies and Henle, on All Soul’s Day, were visiting their colleague and fellow priest Georg Maria Stenz. Within two weeks of their death, Germany landed an occupying force at Kiaozhou Bay. Germany later compelled the Qing government to remove a regional governor, build three new Catholic churches, and pay a reparation of 3,000 taels. Later the singularity of the Juye incident, so-called, was blurred by the emergence of the broader and more coherent uprising Yihequan Movement, the Boxer Uprising, of 1899-1901. Simultaneously, Germany negotiated—exacted is perhaps a more nearly accurate term—the Kiautschou Bay Concession: a ninety-nine year lease of over two hundred square miles, which, while still belonging to China, were under the sovereignty of Germany. The agreement permitted construction of harbor facilities; a railroad connecting Shantung to Manchuria, and to the Tran-Siberian, and eventually Berlin; coal mining; and the planting of a modern German town.

Вложения

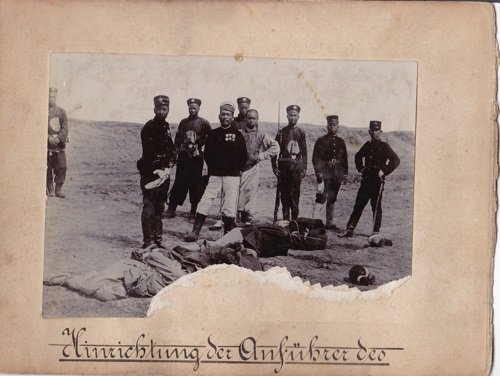

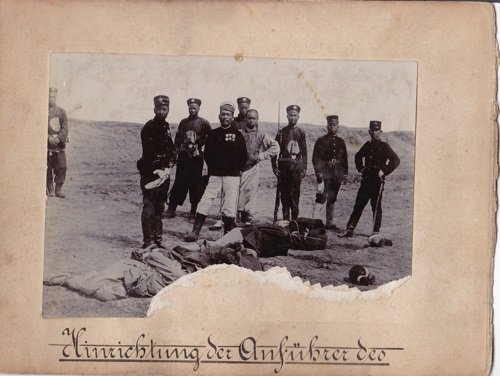

3. The Boxer Uprising, cause and pretext for the European consolidation of power in China, also provided great and lasting rhetorical momentum. This photograph, entitled “Execution of the Leaders of . . .,” dates from 1899-1901, ten years before Albert Facknitz’s arrival. It shows Qing onlookers, decapitated Boxers, and Japanese officers and executioners. Like several of the photographs, this is one was probably purchased, mounted on heavy paper, and titled in a careful hand in old-style German script. Two heads are missing from this copy. Who tore the photograph and why I do not know. I do know that my father as a boy would sometimes sneak into the cupboard and get out the pictures his father brought back from China. This one, he said, riveted him in its grisliness.

The presence of Chinese and Japanese soldiers in the execution photograph remind us of the tensions in the historical moment, particularly in China where the ambiguities of class, language, region, and decadence had not been sorted and simplified as they had been in the nationalizing fervor of Meiji Japan or, for that matter, Bismarck’s Germany. Japan was among the eight nations which expanded their influence in China, especially Shantung and Manchuria, at the time of the Boxer Uprising. Such was the civil and military incoherence among the Chinese that under what circumstances the Chinese soldiers participated in the execution would be impossible to say with certainty.

The presence of Chinese and Japanese soldiers in the execution photograph remind us of the tensions in the historical moment, particularly in China where the ambiguities of class, language, region, and decadence had not been sorted and simplified as they had been in the nationalizing fervor of Meiji Japan or, for that matter, Bismarck’s Germany. Japan was among the eight nations which expanded their influence in China, especially Shantung and Manchuria, at the time of the Boxer Uprising. Such was the civil and military incoherence among the Chinese that under what circumstances the Chinese soldiers participated in the execution would be impossible to say with certainty.

4. Similarly enigmatic is this photograph of a European nurse—she wears the Red Cross medallion at her collar—flanked by women on either side. At first glance, the image seems simply to record the fact of the presence of western women in the colonial drama of the early twentieth century. Who she is, why she is in China, and exactly when the picture was taken and by whom, are details that I cannot recuperate. This recalls the conundrum of women’s history; we know they were present in equal measure to men, but their documentation is sparse by comparison. So, in the absence of contextualizing narrative, frustrated in our desire to know who was this young woman with the modest smile and the good posture, we risk missing some startling details if we accept that her anonymity makes her unreadable. But as text, this photograph is remarkably rich. All the women to her right and the first two to her left are Chinese. The four at the right of the photograph, her left, are Japanese. The Chinese women are younger than the Japanese, not as well dressed, and while the Chinese look at the camera, none of the Japanese do. In other words, a complex cultural and circumstantial dynamic is at work here. That much we can know. What put these thirteen people in the same place and the same time?

Вложения

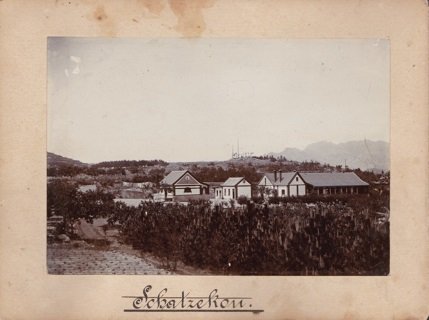

5. This photograph my father once said he thought to be the gate to the old city of Tsingtau. It may have been anywhere, actually, and probably not Tsingtau, as the town was little more than a fishing village when the Germans arrived and began developing a port city, a railroad terminus, and an administrative and military center. By 1910, in China, Tsingtau was second only to Hong Kong in commercial traffic, amenities, cultural diversity, and strategic naval importance. It had massive and domineering new buildings in the Teutonic Imperial manner, but no significant remnants of Chinese antiquity. Still, notably in this photograph, the field of view divides between the awnings and shaded figures on the left (perhaps merchants?) and the waiting rickshaw drivers in the open light on the right. At midpoint, middle distance, there are three men. Two with umbrellas, two in European dress, talking and looking toward the camera.

Вложения

8. Bambushain: bamboo grove. The condition of this picture is even worse, more blurry and bleached than the sunset. The adventure into China, while predictably exotic, seems also to have been sentimental, superficially exotic but archetypally European. A tidy hamlet, a sunset, and a grove mark the ambivalence between alienation and expropriation. What does it mean to fetishize the exotic even while assigning it familiar qualities characterizes several other pictures, still among those that appear to have been purchased and then mounted? Germany’s project of building a modern commercial center and port city, occurred while simultaneously colonizing West Africa and Samoa. Since it is not at all clear that my grandfather stopped in Samoa, it seems likely that his several pictures from there were part of a trade among other Germans.

Вложения

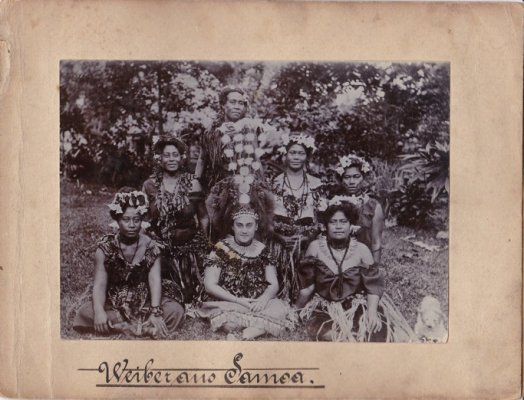

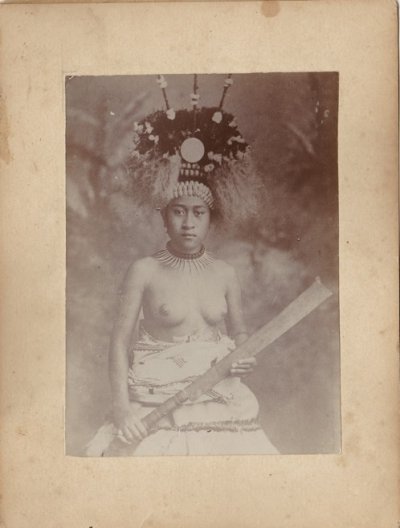

9. In this, Weiberans Samoa, Samoan women, the woman with the elaborate headdress in the middle apparently bore a resemblance to my grandmother, or so thought my father and his older brother.

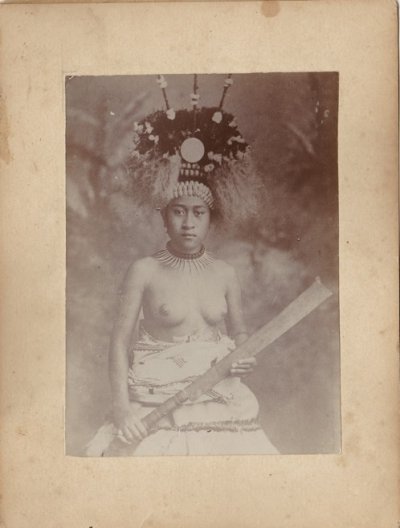

10. The appeal of this one to a soldier bivouacked among men in a foreign garrison is obvious. After release from prison in Japan, more than a hundred of my grandfather’s cohort decided to remain in Japan. Many preferred to emigrate to Samoa.

11. Samoan princess? With headdress and knife, a bemused expression; it is not entirely clear that she knows what she is being asked to represent.

Other photographs in the collection are, it appears, one-offs, certainly not commercially produced, and some of these include my grandfather or members of his company.

10. The appeal of this one to a soldier bivouacked among men in a foreign garrison is obvious. After release from prison in Japan, more than a hundred of my grandfather’s cohort decided to remain in Japan. Many preferred to emigrate to Samoa.

11. Samoan princess? With headdress and knife, a bemused expression; it is not entirely clear that she knows what she is being asked to represent.

Other photographs in the collection are, it appears, one-offs, certainly not commercially produced, and some of these include my grandfather or members of his company.

12. The Germania Brewery, opened in 1904, provided Pilsner beer to the German soldiers and citizens of Tsingtau. In this picture the Chinese man with the palm fan, is not entirely sure of what he is doing or why he is in the middle. Today, the Tsingtao Brewery maintains a sizeable presence in the domestic Chinese market and makes one of China’s principal export beers.

13. Sergeant Wilhelm Schmidt’s squad. Everything suggests that the German troops in Tsingtau were exemplary in matters of morale and unit cohesion—disciplined, vigorous, and dauntless, they were young men who like my grandfather had eluded the near invincible determinants of 19th Century poverty and were now beneficiaries of fresh air, camaraderie, ample food, dry bunks, and steady pay. In finding respect for country and fellow soldiers, they found self-respect. My Opa was a sorrowful man; he was a man of unsurpassed dignity.

14. “The Fun Bunch,” loosely put. The young Chinese male in the lower right seems to have been tugged abruptly toward the soldier to his left at the moment the photograph was taken. Higher up, more beer, and one additional Chinese person. The environment is of rocks and trees; nothing to remark an ambient culture, for the master plan of Tsingtau made China largely invisible behind the robust and vast Bismarck Barracks and spacious Catholic and Lutheran churches.

15. A picturesque and madcap set of poses at seaside. The blurry single Chinese, bottom center, suggests that photographer’s command to hold still was sometimes lost in translation. A special limitation of the photograph as historical evidence is precisely the hegemonic blurring of the cultural topography, so novel and obvious are the contours of the physical landscape. Photographs are deceptive precisely because of their immediacy, their stability.

16. Spreading out over rocks—here at the seaside—seems to have been a motif. My grandfather is just above the penciled arrow.

15. A picturesque and madcap set of poses at seaside. The blurry single Chinese, bottom center, suggests that photographer’s command to hold still was sometimes lost in translation. A special limitation of the photograph as historical evidence is precisely the hegemonic blurring of the cultural topography, so novel and obvious are the contours of the physical landscape. Photographs are deceptive precisely because of their immediacy, their stability.

16. Spreading out over rocks—here at the seaside—seems to have been a motif. My grandfather is just above the penciled arrow.

With the assistance of the British, the Japanese began a naval blockade of Tsingtao at the end of August, 1914, a few weeks after the declaration of war in Europe. In the first week of September Japan began to land the 18th Division of Infantry at Lungkow and Laoshan Bay. The Germans, outnumbered by more than six to one, prepared to defend Tsingtau. At this moment my grandfather, disguised in civilian dress, made his way by train back to Tsingtau from Tientsin, where he had been attached to a diplomatic guard unit. Well-provisioned, the Germans spent September and October waiting, establishing trenches lines, redoubts, and artillery batteries. In 1915, American journalist Jefferson Jones wrote of Tsingtau that “Germany has . . . been forced to surrender all this magnificent work,” and “the Tsingtau of 1914 will clearly standout in the memory of its visitors and Far Easterners as the finest, the prettiest, most modern and sanitary city in the Orient” (153). Post-war, still believing in the promise of the city, several dozen of my grandfather’s fellow P-O-W’s came back to Tsingtau to settle.

The photographs from this moment make plain the severity of landscape as well as the remarkable similarity of German defenses in China to the trenches of the Western Front.

17. Machine gunners take up a position in the rocks and wait.

18. Front line troops before the siege. A defensive position that is downhill of the advancing infantry is not ideal, though this may have been an opportunistic position, either for the camera or because the soldiers could use agricultural terracing as breastworks.

19. From what appears to be a much more tenable position, a German lieutenant surveys the terrain.

The photographs from this moment make plain the severity of landscape as well as the remarkable similarity of German defenses in China to the trenches of the Western Front.

17. Machine gunners take up a position in the rocks and wait.

18. Front line troops before the siege. A defensive position that is downhill of the advancing infantry is not ideal, though this may have been an opportunistic position, either for the camera or because the soldiers could use agricultural terracing as breastworks.

19. From what appears to be a much more tenable position, a German lieutenant surveys the terrain.

20. Troops in a defensive drill. Once combat began in serious, 31 October 1914, the Japanese advanced steadily, and while the German garrison had ample food and medical provisions, they soon exhausted their artillery shells and were compelled to surrender. My grandfather’s right cheek was grazed by a bullet; at one point debris from a shell burst landed so heavily on him that he asked a comrade if his legs were gone. In fact, they were merely bruised.

German casualties included two hundred dead and five hundred wounded compared to more than seven hundred Japanese and British dead, a ratio consistent with casualty comparisons between defensive and offensive troops in the European theater. Most of the German Imperial ships had previously left for Europe; however, a remaining cruiser, torpedo boat, and four gunboats were scuttled by their crews before the German surrender on 7 November. All the men of the Third German Sea Battalion were taken prisoner and shipped to Japan. In Europe the sea battalions were put into the lines in Flanders and inflated to the size of divisions, eventually two marine divisions known as the Marine-Korps-Flandern, totaling seventy thousand troops. Had he been in Europe, rather than a P.O.W. camp, my grandfather likely would have been exposed to action at Yprès in 1915, or the Somme the next year, or in Flanders the year after that, and, on the slim chance he would still be alive, in the final desperate offensive of early 1918, he might have fought in the Kaiserschlacht. Instead, he experienced relatively good treatment in Japan, first for almost a year at Asakusa (now in central Toyko), and for the rest of the war and all of 1919 at a camp thirty kilometers away in Narashino.

21. The gatehouse of the Narashino prisoner of war camp. Compared to Asakusa—converted crowded and outdated Japanese barracks—Narashino, a large camp, purpose built, housed nearly a thousand, with sports facilities, camp library, and orchestra and chorus. My grandfather belonged to the Tischler-Innung Narashino, a cabinet maker’s guild. In addition to numerous chess sets, which he gave to his captors and his comrades, he made a dozen violins. The boundaries of the camp were remarkably fluid; the prisoners worked with local farmers and gardeners, sharing ideas from German horticultural practices. (My grandfather treasured his rose bushes in later life.) Ordinary soldiers received half a yen a day which allowed them to purchase tobacco and soap.

22. The washhouse at Narashino, for bodies and clothing. Except for the influenza in 1918, staying healthy was not a particular challenge.